Page 115 - 34-1

P. 115

(over-reserve less). We include a variable to capture effects of net income smoothing in the model,

(over-reserve less). We include a variable to capture effects of net income smoothing in the model,

which is defined as the difference between unbiased net income in year t and reported net income

which is defined as the difference between unbiased net income in year t and reported net income

in year t-1 divided by the absolute value of reported net income in year t-1 (Gaver and Paterson,

in year t-1 divided by the absolute value of reported net income in year t-1 (Gaver and Paterson,

2014). That is, unbiased net income in the current year reflects net income without the loss

2014). That is, unbiased net income in the current year reflects net income without the loss

reserving error; it is an estimate of actual net income. We expect this variable to be positively

reserving error; it is an estimate of actual net income. We expect this variable to be positively

related to the loss reserve error.

related to the loss reserve error.

Two competing hypotheses exist in prior literature as to how rate regulation is related to

Two competing hypotheses exist in prior literature as to how rate regulation is related to

NTU Management Review Vol. 34 No. 1 Apr. 2024

loss reserve errors (i.e., Nelson, 2000; Grace and Leverty, 2010). Nelson (2000) posits that under-

loss reserve errors (i.e., Nelson, 2000; Grace and Leverty, 2010). Nelson (2000) posits that under-

reserving takes place in rate-regulated lines because insurers are interested in convincing

reserving takes place in rate-regulated lines because insurers are interested in convincing

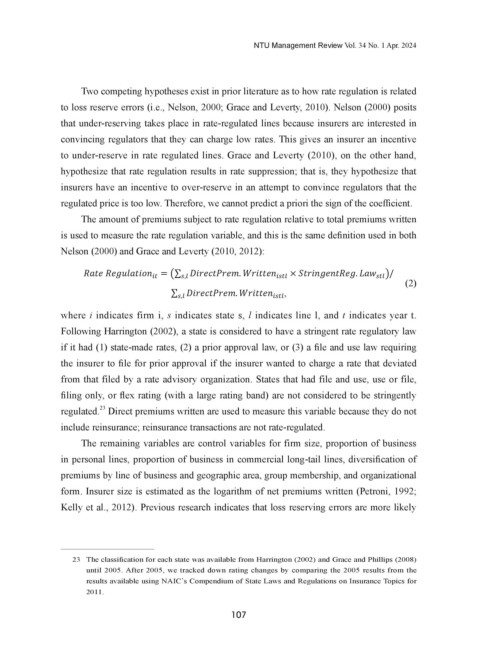

Two competing hypotheses exist in prior literature as to how rate regulation is related

regulators that they can charge low rates. This gives an insurer an incentive to under-reserve in

regulators that they can charge low rates. This gives an insurer an incentive to under-reserve in

to loss reserve errors (i.e., Nelson, 2000; Grace and Leverty, 2010). Nelson (2000) posits

rate regulated lines. Grace and Leverty (2010), on the other hand, hypothesize that rate regulation

rate regulated lines. Grace and Leverty (2010), on the other hand, hypothesize that rate regulation

that under-reserving takes place in rate-regulated lines because insurers are interested in

convincing regulators that they can charge low rates. This gives an insurer an incentive

results in rate suppression; that is, they hypothesize that insurers have an incentive to over-reserve

results in rate suppression; that is, they hypothesize that insurers have an incentive to over-reserve

to under-reserve in rate regulated lines. Grace and Leverty (2010), on the other hand,

in an attempt to convince regulators that the regulated price is too low. Therefore, we cannot

in an attempt to convince regulators that the regulated price is too low. Therefore, we cannot

hypothesize that rate regulation results in rate suppression; that is, they hypothesize that

predict a priori the sign of the coefficient.

predict a priori the sign of the coefficient.

insurers have an incentive to over-reserve in an attempt to convince regulators that the

regulated price is too low. Therefore, we cannot predict a priori the sign of the coefficient.

The amount of premiums subject to rate regulation relative to total premiums written is

The amount of premiums subject to rate regulation relative to total premiums written is

The amount of premiums subject to rate regulation relative to total premiums written

used to measure the rate regulation variable, and this is the same definition used in both Nelson

used to measure the rate regulation variable, and this is the same definition used in both Nelson

is used to measure the rate regulation variable, and this is the same definition used in both

(2000) and Grace and Leverty (2010, 2012):

Nelson (2000) and Grace and Leverty (2010, 2012):

(2000) and Grace and Leverty (2010, 2012):

= �∑

× �/

= �∑ ���� × �/ ���

����

��

���

��

���

���

(2)

∑ , (2)

���

����

∑ ���� , (2)

���

where i indicates firm i, s indicates state s, l indicates line l, and t indicates year t.

Following Harrington (2002), a state is considered to have a stringent rate regulatory law

where i indicates firm i, s indicates state s, l indicates line l, and t indicates year t. Following

where i indicates firm i, s indicates state s, l indicates line l, and t indicates year t. Following

if it had (1) state-made rates, (2) a prior approval law, or (3) a file and use law requiring

Harrington (2002), a state is considered to have a stringent rate regulatory law if it had (1) state-

Harrington (2002), a state is considered to have a stringent rate regulatory law if it had (1) state-

the insurer to file for prior approval if the insurer wanted to charge a rate that deviated

from that filed by a rate advisory organization. States that had file and use, use or file,

made rates, (2) a prior approval law, or (3) a file and use law requiring the insurer to file for prior

made rates, (2) a prior approval law, or (3) a file and use law requiring the insurer to file for prior

filing only, or flex rating (with a large rating band) are not considered to be stringently

regulated. Direct premiums written are used to measure this variable because they do not

23

18 18

include reinsurance; reinsurance transactions are not rate-regulated.

The remaining variables are control variables for firm size, proportion of business

in personal lines, proportion of business in commercial long-tail lines, diversification of

premiums by line of business and geographic area, group membership, and organizational

form. Insurer size is estimated as the logarithm of net premiums written (Petroni, 1992;

Kelly et al., 2012). Previous research indicates that loss reserving errors are more likely

23 The classification for each state was available from Harrington (2002) and Grace and Phillips (2008)

until 2005. After 2005, we tracked down rating changes by comparing the 2005 results from the

results available using NAIC’s Compendium of State Laws and Regulations on Insurance Topics for

2011.

107