從動態競爭觀點審視作業流程管理的創新與改進

22

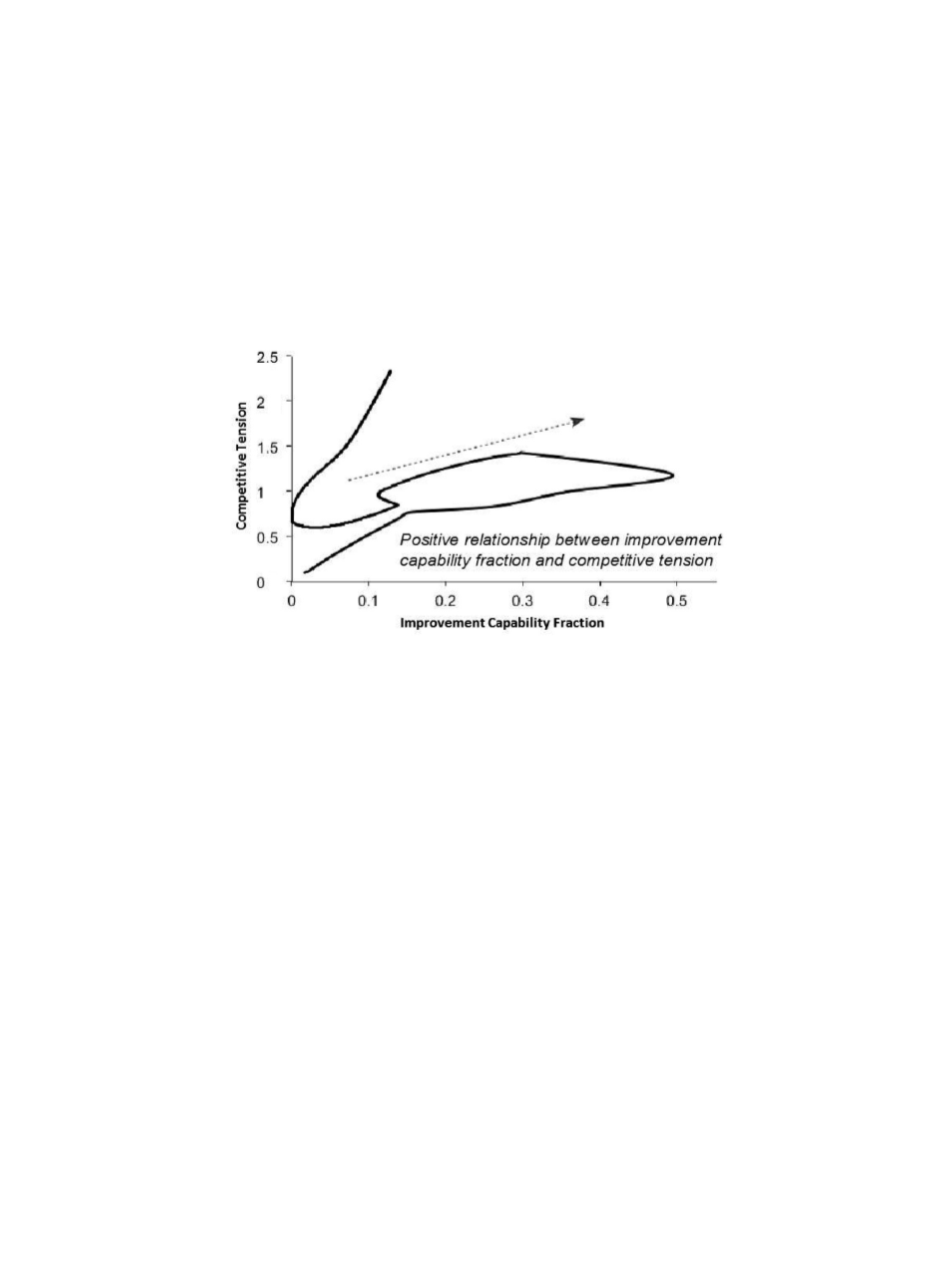

alleviates the competitive tension (Chen and MacMillan, 1992). By comparing different

capability development trade-offs (Figures 2 to 4), however, our analysis shows the opposite

outcomes: surprisingly, through the phase plot analysis (Figure 8), we find the follower’s

investment in improvement capability may relax the competitive tension, a counterintuitive

positive relationship.

Figure 8 The Impact of Improvement Capability Fraction on Competitive Tension

Now consider process improvement, as illustrated in Figures 2b and 3a. Indeed, by

developing process improvement capabilities, the follower clearly signals its attempt to

eliminate operational inefficiencies. It invests massive resources, signaling high internal

commitment, to achieve this objective. Yet such improvement occurs within the current

frontier rather than by creating a new frontier (i.e., a new best practice) (Swink and Hegarty,

1998). Therefore, this is rather good news to the leader since he/she needs not to worry about

being dethroned. In other words, the followerʼs apparent public commitment to its

investment discourages the leader from reacting aggressively. Consequently, the follower

falls into improvement inertia so that resource similarity increases and the intensity of

competition decreases in the long run (as illustrated in Figures 2f and 3b). In terms of

process innovation capabilities, the follower publicly commits to developing new processes

that go beyond the frontier occupied by the leader. The followerʼs ultimate objective is to

compete with and surpass the leader for rent generation. Therefore, the leader expects to

engage in direct competition as long as the follower achieves any positive outcome through

developing innovation capabilities (see Figure 4b). Formally,